How a tiny worm changed a decade of scientific thinking

A tiny roundworm has helped Australian scientists rethink the way sensory nerve connections remain strong throughout a lifetime.

With the help of a tiny roundworm, scientists at The University of Queensland (UQ) have uncovered miniscule structures in skin tissue that may protect the body’s ability to feel temperature, touch and pain; leading to research that, the university says, changes a decade of scientific thinking on the way sensory nerve connections remain strong throughout a lifetime.

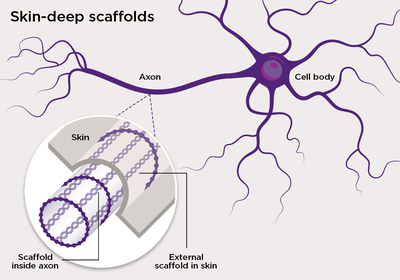

The discovery of an external protective ‘scaffold’ in the skin that surrounds sensory nerves has, according to Dr Sean Coakley from UQ’s School of Biomedical Sciences, given a glimpse of how the skin and nervous system work together to protect the cable-like structures which receive and transmit messages back to the brain.

“If these axons are damaged, signals that transmit sensory information like touch, temperature and pain are disrupted with potentially devastating impact, as we see in both traumatic injuries and neurodegenerative diseases,” Coakley said. “Axons are very long and thin, and in humans they can reach up to a metre in length but they’re only one-fiftieth of the width of a hair.

“This should make them extremely vulnerable to damage, yet they withstand a lifetime of constant strain as our body moves, flexes and absorbs impacts in everyday tasks,” Coakley added. “Understanding how they are protected is important for future therapies to treat nervous-system injuries and disease.”

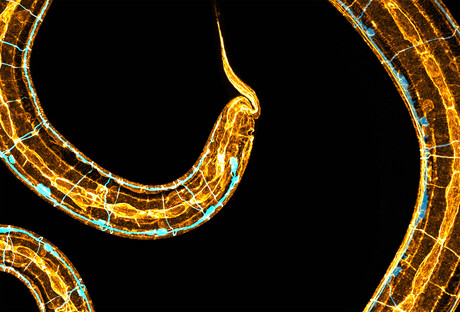

Humans and other species have sensory axons embedded in the skin, the body’s largest organ, like in the roundworm C. elegans. This worm is tiny — only about one millimetre long — and the research team was able to reveal an internal scaffolding structure in the skin around the axons with super resolution microscopy.

“This scaffold appears to shield the axons in a similar way to a plaster cast protecting a broken arm,” Professor Massimo Hilliard from UQ’s Queensland Brain Institute said, explaining that the scaffold of nano-scale trusses and beams was made from protein molecules known as spectrins. “Until now, we thought that axons were robust because they had an internal scaffold that made them elastic and able to stretch when needed.

“Now, we think that this is not enough,” Hilliard added. “The external scaffold present in the skin that we have discovered appears to be critically important for maintaining the integrity of these tiny underlying cables.”

According to Dr Igor Bonacossa Pereira from UQ’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience, this knowledge may inform and re-direct existing and new therapies aimed at protecting axonal structure and function.

“Focusing on the tissue surrounding the axon might uncover new ways of treating and preventing injury and disease,” Pereira said. “All animals have spectrins, which suggests these molecules are a key building block and will now be the subject of significant further study.”

This research was published open access (doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adz4762) in Science Advances and features on the journal’s cover.

Aussie biotech to manufacture mRNA paediatric brain cancer vaccines

A Queensland-based biotechnology company will manufacture personalised mRNA paediatric brain...

Who's afraid of killer whales? — white sharks and prolonged absences

Is killer whale predation the sole driver of white shark long absence? Australian researchers...

Five scenarios for the future of Antarctic life

A team of Australian and international researchers have predicted five possible outcomes for how...