Gut microbiome–autism link flipped on its head

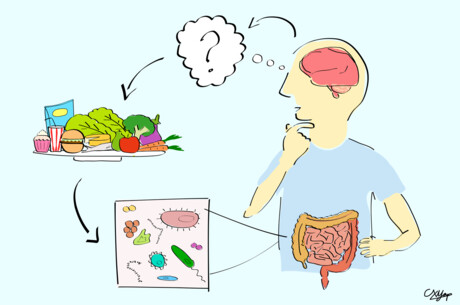

While some scientists have suggested that autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may be at least partly caused by differences in the composition of the gut microbiota, based on the observation that certain types of microbes are more common in people with autism, Australian researchers have said that this link may actually work the other way around.

The new study claims that the diversity in species found in the guts of children with autism may be due to their restricted dietary preferences, rather than the cause of their symptoms. The research was funded by the Autism CRC and led by Mater Research and The University of Queensland (UQ), with findings published in the journal Cell.

Over the past decade, as next-generation sequencing of the microbial species in the gut has made analysis of the microbiome more automated and less time-consuming, a number of studies have examined the link between particular species of microbes in the gut and mental health. The gut–brain axis has been linked not only to ASD but also to anxiety, depression and schizophrenia. The possibility of targeting the microbiota is thus a growing area of research for new treatments.

“There’s been a lot of hype around the gut microbiome in autism in recent years — driven by reports that autistic children have high rates of gut problems — but that hype has outstripped the evidence,” said senior author Dr Jacob Gratten, Head of Mater Research’s Cognitive Health Genomics Group.

“Our study, which is the largest to date, was designed to overcome some of the limitations of prior work.”

The investigators analysed stool samples from a total of 247 children between the ages of two and 17. The samples were collected from 99 children diagnosed with ASD, 51 paired undiagnosed siblings, and 97 unrelated, undiagnosed children. The subjects included in the analysis were from the Australian Autism Biobank and Queensland Twin Adolescent Brain Project.

The investigators analysed the samples by metagenomic sequencing, which looks at the entire genome of microbial species rather than short genetic barcodes (as with 16S analysis). It also provides gene-level information rather than just species-level information, and provides a more accurate representation of microbiome composition than 16S analysis, a technique used in many of the earlier studies linking the microbiome to autism.

“We also carefully accounted for diet in all our analyses, along with age and sex,” said first author Chloe Yap, who is completing her medical degree and PhD at UQ. “The microbiome is strongly affected by the environment, which is why we designed our study with two comparison groups.”

Based on their analysis, the researchers found limited evidence for a direct association of autism with the microbiome. Indeed, Dr Gratten said that out of more than 600 bacterial species identified in the gut microbiomes of study participants, only one was associated with a diagnosis of ASD.

However, the researchers did find a highly significant association of autism with diet and that an autism diagnosis was associated with less diverse diet and poorer dietary quality; ‘fussy eating’ is common among autistic children due to sensory sensitivities or restricted and repetitive interests. Moreover, psychometric measures of degree of autistic traits (including restricted interests, social communication difficulties and sensory sensitivity) and polygenic scores (representing a genetic proxy) for ASD and impulsive/compulsive/repetitive behaviours were also related to a less diverse diet.

“While it’s a popular idea that the microbiome affects behaviour, our findings flip that causality on its head,” Yap said.

“We found that children with an autism diagnosis tended to be pickier eaters, which led them to have a less diverse microbiome. This in turn was linked to more watery stools. So, our data suggests that behaviour and dietary preferences affect the microbiome, rather than the other way around.”

Dr Gratten hopes the study will put the brakes on the experimental use of microbiome-based interventions, such as faecal microbiota transplants and probiotics, that some believe may treat or minimise autistic behaviours. He noted, “We are already seeing early clinical trials involving faecal microbiota transplants from non-autistic donors to autistic people, despite not actually having evidence that the microbiome drives autism. Our results suggest that these studies are premature.”

Autism CRC Research Strategy Director Professor Andrew Whitehouse said the study findings provide impressive clarity to an area that has been shrouded in mystery and controversy.

“Families are desperately seeking new ways to support their child’s development and wellbeing,” he said. “Sometimes that strong desire can lead them to diet or biological therapies that have no basis in scientific evidence.

“The findings of this study provide clear evidence that we need to help support families at mealtimes, rather than trying fad diets. This is a hugely important finding.”

The researchers acknowledge that the design of their study can’t rule out microbiome contributions prior to ASD diagnosis, nor the possibility that diet-related changes in the microbiome have a feedback effect on behaviour. Another limitation is that they could only account for the possible effect of antibiotics on the microbiome by excluding those taking these medications at the time of stool collection. Finally, no comparable datasets are currently available to confirm the findings. The researchers plan to generate new data in a larger sample to replicate their findings.

“We hope that our findings encourage others in the autism research community to routinely collect metadata in ‘omics’ studies to account for important (but often underappreciated) potential confounders such as diet,” Dr Gratten said. “Our results also put the spotlight on nutrition for children diagnosed with autism, which is a clinically important (but under-recognised) contributor to overall health and wellbeing.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Five scenarios for the future of Antarctic life

A team of Australian and international researchers have predicted five possible outcomes for how...

Could this biosensor bypass labs with onsite PFAS detection?

La Trobe University has developed a portable biosensor that may allow rapid, onsite detection of...

How a tiny worm changed a decade of scientific thinking

A tiny roundworm has helped University of Queensland scientists rethink the way sensory nerve...