What makes some cancer cells dormant?

An international team of scientists has uncovered the unique set of genes that keeps some cancer cells dormant. Published in the journal Blood, their research may reveal new therapeutic targets for cancers such as multiple myeloma, as well as breast and prostate cancer.

Most will associate cancer with its fast growing cells that spread uncontrollably — but in fact, it’s often the cancer cells that are dormant and inactive that pose the greatest threat. Dormant cancer cells, when ‘woken up’, are a major cause of cancers coming back, or relapsing, after treatment — often as metastases, which are estimated to cause 90% of all cancer deaths.

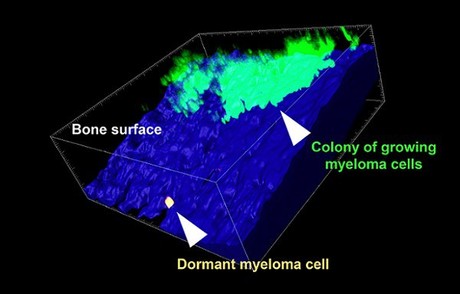

When cancer metastasises, it spreads to different organs in the human body. Some cancer cells can stop dividing and hide in a ‘dormant’ state, tucked away in niches such as the inner lining of bones. Once dormant, the immune system cannot find them to target them and conventional chemotherapy is ineffective. There is also no way of knowing how long the cells will remain dormant.

To help prevent dormant cancer cells from being reactivated, scientists led by Sydney’s Garvan Institute of Medical Research are investigating what makes these cells dormant in the first place. But isolating the cells to study them has been a challenge — they are rare, often less than one in hundreds of thousands of cells in the bone, and scientists have not known how to identify them.

“What makes our approach different is that we’re looking at the cancer ecosystem as a whole,” said Associate Professor Tri Phan, co-senior author of the new study. “It’s not just the cancer cell but the other cells in their microenvironment which determine their fate. We are trying to find what genes get switched on by the microenvironment and how those genes make the cancer cell dormant.”

The Garvan researchers first developed a way to track dormant multiple myeloma cells inside the bones of living mice four years ago using a new technique called intravital two-photon microscopy. They have now isolated these rare cells to analyse the dormant cells’ transcriptome — a snapshot of all the genes that are switched on in the cell and control dormancy.

“Having been able to identify the rare dormant cells, we were able to isolate them and work out all the genes which were active,” said Dr Weng Hua Khoo, first author of the study. “What is exciting is that we discovered many of these genes in dormant cells are not normally switched on in these cancer cells. Now that we know the identity of these genes, we can use that information to target them.”

The team analysed the single-cell transcriptomes at the Garvan-Weizmann Centre for Cellular Genomics and confirmed their findings independently with their collaborators at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science. Unexpectedly, the dormant myeloma cells had a similar transcriptome signature to immune cells, but were only ‘switched on’ when the cells were located next to osteoblasts — specialised cells found in bone.

“This showed us just how crucial the crosstalk between the tumour cells and the tumour microenvironment is for cancer dormancy,” said Professor Ido Amit, Principal Investigator at the Weizmann Institute.

The researchers are now using their method to collect data on dormant cancer cells from other cancer types, with the hope of finding a common signature that would allow them to target all dormant cancer cells. Garvan Research Director Professor Peter Croucher said, “The aim now is to bring data from many cancer types together to find a unifying approach to understanding how dormant cells control cancer relapse and metastasis.” The team is also working to develop potential therapies that target the unique features of dormant cells, now uncovered by this research.

“There are different approaches to targeting dormant cells,” Prof Croucher said. “One is to keep them dormant indefinitely by creating an environment that stops them from waking up. A second approach is to deliberately wake them up, which can then make them susceptible to being targeted with conventional chemotherapy. But the best approach would be to use this knowledge of what the genes are that keep cells in the dormant state to eradicate them while they’re dormant. This would stop the disease coming back or relapsing — this would be the Holy Grail.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Aussie biotech to manufacture mRNA paediatric brain cancer vaccines

A Queensland-based biotechnology company will manufacture personalised mRNA paediatric brain...

Who's afraid of killer whales? — white sharks and prolonged absences

Is killer whale predation the sole driver of white shark long absence? Australian researchers...

Five scenarios for the future of Antarctic life

A team of Australian and international researchers have predicted five possible outcomes for how...