The cause of a common female infection

Researchers from St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research (SVI) have led a study which shows how the bacteria Gardnerella vaginalis targets cells and causes infection in women. Their work has been published in the journal Structure.

Gardnerella vaginalis is the bacteria primarily responsible for bacterial vaginosis (BV), the most common vaginal infection worldwide. One of the bacteria’s tools for establishing infection is the protein toxin vaginolysin. Using small-angle X-ray scattering at the Australian Synchrotron, SVI researchers were able to track the journey from toxin to infection.

“The research found that the toxin vaginolysin — which, unlike many other common toxins, only targets human tissues — is attracted to cells that have the receptor protein CD59 on their surface,” said co-lead author Dr Craig Morton. “The normal role of CD59 is to ‘turn down’ the body’s immune system so that it doesn’t attack cells that don’t pose a threat. Vaginolysin has hijacked this activity, allowing the bacteria to use this protective mechanism to single out human cells.

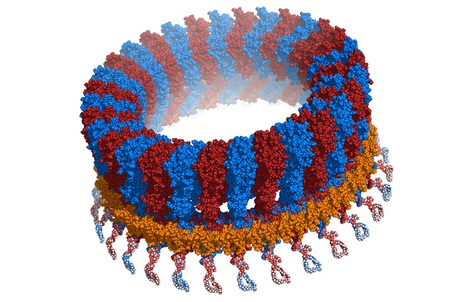

“Once vaginolysin starts aggregating on CD59, it forms rings and punches holes in the cell membrane. This allows the cell’s essential nutrients to leak out. The bacteria then feed off of the nutrients and infect the epithelial layers, causing bacterial vaginosis.”

According to co-lead author and team head Professor Michael Parker, the study could have far-reaching impacts on human health — an especially timely development as the rise of superbugs makes antibiotic treatment of infections a less appealing option going forward.

“It provides us with not one, but three areas of potential research,” he said. “For example, identifying how the toxin works may lead to the development of a vaccine to prevent the infection.

“This research also has the potential to help us develop therapeutic approaches to ‘control’ how the toxin works and cause the Gardnerella bacteria to become less virulent. By blocking the toxin, the bacteria would still be there, but unable to cause significant disease.

“Another exciting way we can use this knowledge is to attempt to ‘engineer’ this toxin, so that it becomes specific for markers other than CD59 such as those found on tumours, and could potentially be used to destroy the cancer cells.”

Noxopharm says paper reveals science behind its immune system platform

Clinical-stage Australian biotech company Noxopharm Limited says a Nature Immunology...

Neurosensing/neurostimulation implants session to be held on Monday

On Monday, a session at UNSW Sydney will include people who are benefiting from bioelectronics...

argenx and Monash University partner against autoimmune diseases

To advance a pioneering molecule for autoimmune diseases, global immunology company argenx has...