Two new blood tests for Alzheimer's developed

Researchers from both Singapore and Sweden have, within a day of each other, announced their own blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) — the most common type of dementia.

Due to the complex and progressive nature of AD, early detection and intervention can improve the success of disease-modifying therapies. Unfortunately, current AD diagnosis and monitoring — in the form of clinical evaluation and neuropsychological assessments — is subjective, and the disease tends to be detected at a late stage. More reliable alternatives, such as PET brain imaging and cerebrospinal fluid tests, are either too expensive for wide clinical adoption or require invasive lumbar punctures.

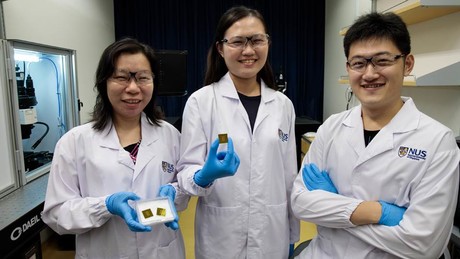

Blood-based tests, on the other hand, have the advantage of being safe, affordable and easy to administer. But blood has very low concentrations of AD molecules and not all of these molecules are disease-reflective, meaning detection and diagnosis remains difficult. That could all be about to change with the APEX (Amplified Plasmonic EXosome) system, invented by Assistant Professor Shao Huilin and her team from the National University of Singapore (NUS) and described in the journal Nature Communications.

A key characteristic of AD is the build-up of amyloid beta (Aβ) proteins in the brain, which clump up as aggregates and kill brain cells. Aβ proteins are also released into and circulate through the bloodstream. The APEX system is designed to detect and analyse the earliest aggregated forms of Aβ proteins in blood samples, to enable detection of AD even before clinical symptoms appear and to accurately classify the disease stages.

“Traditional technologies measure all Aβ molecules found in the blood, regardless of their aggregation states, and thus show poor correlation to brain pathology,” said doctoral student Carine Lim, co-first author of the study. “Our study found that the aggregated form of the protein could accurately reveal brain changes and reflect AD disease stages.”

The APEX technology is size-matched to distinguish this group of reflective Aβ proteins directly from blood samples. Each APEX chip is 3 x 3 cm — about a quarter the size of a credit card — and contains 60 neatly arranged sensors, each to analyse one blood sample.

“Within each APEX sensor, there are millions of nanoholes to enable unique interactions with the aggregated Aβ,” said doctoral student Zhang Yan, co-first author of the study. “The APEX sensor recognises the abnormal Aβ aggregates directly from a very small amount of blood, induces and amplifies a colour change in the associated light signal.”

To determine the performance of the APEX system, Asst Prof Shao and her team conducted a clinical study involving 84 individuals, including patients who have been diagnosed with AD or mild cognitive impairment (MCI), as well as a control group comprising healthy individuals and patients diagnosed with vascular dementia or neurovascular compromises. PET imaging and blood sampling were conducted on all participants.

“The results of the APEX tests correlate extremely well with PET imaging results,” Asst Prof Shao said. “The clinical study shows that the APEX system can accurately identify patients with AD and those with MCI; it also differentiates them from healthy individuals and patients suffering from other neurodegenerative diseases. In fact, this is the only blood test that shows such comparable results with PET imaging, the current gold standard for AD diagnosis.”

As the APEX system uses native blood plasma without additional sample processing, it conducts direct measurement and is very simple to use in clinical settings. It is also highly sensitive and provides an accurate diagnosis at about $30 per test, which is less than 1% of the cost of PET imaging. The current design could test 60 samples simultaneously, with the results available in less than 1 h.

Asst Prof Shao and her team are currently in discussions with industry partners to commercialise the technology, which they expect to reach market within the next five years. In the next phase of research, the team hopes to employ the technology in areas of AD disease management, as well as for evaluation of AD therapeutics under development.

Meanwhile, researchers from Sweden’s Lund University have partnered with pharmaceutical company Roche on the development of their own blood marker capable of detecting whether or not a person has AD, based on an accumulation of Aβ in the brain. The team will soon commence a trial in primary health care to test the technique, which has been described in the journal JAMA Neurology.

“Previous studies on methods using blood tests did not show particularly good results; it was only possible to see small differences between Alzheimer’s patients and healthy elderly people,” said Associate Professor Sebastian Palmqvist, lead author of the study. “Only a year or so ago, researchers found methods using blood sample analysis that showed greater accuracy in detecting the presence of Alzheimer’s disease. The difficulty so far is that they currently require advanced technology and are not available for use in today’s clinical procedures.”

The method studied by Palmqvist and his colleagues was developed by Roche and is a fully automated technique which measures Aβ in the blood, with high accuracy in identifying the protein accumulation. Their results are based on studies of blood analyses collected from 842 people in Sweden and 237 people in Germany, including Alzheimer’s patients, healthy elderly people and people with MCI.

The researchers believe that their simple and precise method could be useful for screening individuals for inclusion in clinical drug trials for Alzheimer’s disease or to improve diagnostics in primary care, which will allow more people to get the currently available symptomatic treatment.

“The next step to confirm this simple method to reveal beta-amyloid through blood sample analysis is to test it in a larger population where the presence of underlying Alzheimer’s is lower,” Palmqvist said. “We also need to test the technique in clinical settings, which we will do fairly soon in a major primary care study in Sweden. We hope that this will validate our results.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Could this 'PFAS trap' remove the most difficult-to-capture variants from water?

Flinders University scientists have showcased the use of a nano-sized molecular cage that acts as...

What journalists expect from the scientists they speak to

Peer review is often treated as the end of the story, but for journalists it is usually the point...

European Space Agency inaugurates deep space antenna in WA

The ESA has expanded its capability to communicate with scientific, exploration and space safety...