AI helps predict the effect of antidepressants

Why do antidepressants work in some people, but not others? It’s a question psychiatrists have been asking for years, and now researchers from UT Southwestern Medical Center may have the answer.

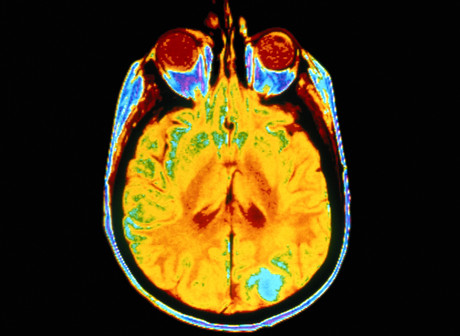

The researchers have used artificial intelligence to identify patterns of brain activity that make people less responsive to certain antidepressants. Their studies include findings from the 16-week EMBARC trial, intended to establish biology-based, objective strategies to remedy mood disorders and minimise the trial and error of prescribing treatments.

“We need to end the guessing game and find objective measures for prescribing interventions that will work,” said Dr Madhukar Trivedi, who oversees EMBARC and is founding director of UT Southwestern’s Center for Depression Research and Clinical Care.

The two studies — which each included more than 300 participants — used imaging to examine brain activity in both a resting state and during the processing of emotions. Both studies divided the participants into a healthy control group and people with depression who either received antidepressants or placebo. Of the participants who received medication, researchers found correlations between how the brain is wired and whether a participant was likely to improve within two months of taking an antidepressant.

Dr Trivedi said imaging the brain’s activity in various states is important to get a more accurate picture of how depression manifests in a particular patient. For some people, he said, the more relevant data will come from their brains’ resting state, while in others the emotional processing will be a critical component and a better predictor for whether an antidepressant will work.

“Depression is a complex disease that affects people in different ways,” he said.

EMBARC’s first study, published in JAMA Psychiatry, focused on how electrical activity in the brain can indicate whether a patient is likely to benefit from an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor), the most common class of antidepressant. The finding was followed by related research that identifies other predictive tests for SSRIs, most recently the resting-state brain imaging study published in The American Journal of Psychiatry and the second imaging study published in Nature Human Behaviour.

The Nature research used artificial intelligence to determine correlations between the effectiveness of an antidepressant and how a patient’s brain processes emotional conflict. Participants undergoing brain imaging were shown photographs in quick succession that offered sometimes conflicting messages such as an angry face with the word ‘happy’, or vice versa. Each participant was asked to read the word on the photograph before clicking to the next image.

However, rather than observe only neural regions believed to be relevant to predicting antidepressant benefits, scientists used machine learning to analyse activity in the entire brain. “Our hypotheses for where to look have not panned out, so we wanted to try something different,” Dr Trivedi explained.

AI identified specific brain regions — for example, in the lateral prefrontal cortices — that were most important in predicting whether participants would benefit from an SSRI. The results showed that participants who had abnormal neural responses during emotional conflict were less likely to improve within eight weeks of starting the medication.

Dr Trivedi’s team hopes to use their various test results to augment brain imaging and more accurately assess patients’ biological signatures to determine the most effective treatment. Dr Trivedi has had preliminary success developing a blood test but acknowledges it may only benefit patients with a specific type of inflammation; combining blood and brain tests should therefore improve the chances of choosing the right treatment the first time, he said.

“We need to look at this issue in several ways to identify the many different signatures of depression in the body,” he said. “The findings from these new studies are significant and bring us closer to using them clinically to improve outcomes for millions of people.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

Beckman Coulter Life Sciences announces Automata partnership

Beckman Coulter Life Sciences has announced a strategic partnership with Automata — to...

AI spots hidden objects in chest scans

A new artificial intelligence (AI) tool can spot hard-to-see objects lodged in patients'...

Drying biofluid droplets used to diagnose disease

A newly developed workflow relies on the drying process of biofluid droplets to distinguish...