Why do antibiotics have side effects?

Over the years, doctors have prescribed antibiotics freely, thinking that they harm bacteria while leaving human tissue unscathed. But as scientists at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering have noted, “Prolonged antibiotic treatment can lead to detrimental side effects in patients, including ototoxicity, nephrotoxicity and tendinopathy.”

The reason for these side effects has, until recently, remained unclear. Now, the Wyss Institute team has discovered not only the reason for the side effects, but also two ways of stopping them. Their research has been published in Science Translational Medicine.

“Clinical levels of antibiotics can cause oxidative stress that can lead to damage to DNA, proteins and lipids in human cells, but this effect can be alleviated by antioxidants,” said Dr Jim Collins, who led the study. Oxidative stress is a condition in which cells produce chemically reactive oxygen molecules that damage the bacteria’s DNA and enzymes, as well as the membrane that encloses the cell.

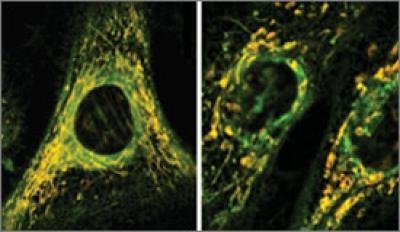

Dr Collins’ team had already discovered that antibiotics that kill bacteria do so by triggering oxidative stress in the bacteria; they then wondered whether the antibiotics also trigger oxidative stress in the mitochondria - a bacterium-like organelle that supplies human cells with energy - thus causing the side effects.

Dr Sameer Kalghatgi and Catherine S Spina first tested whether clinical levels of three antibiotics - ciprofloxacin, ampicillin and kanamycin - caused oxidative stress in cultured human cells. They found that all of these drugs were safe after six hours of treatment, but longer-term treatment of about four days caused the mitochondria to malfunction. They then ran biochemical tests which showed that the same three antibiotics damaged the DNA, proteins and lipids of cultured human cells - exactly what one would expect from oxidative stress.

The team also treated mice with the same three antibiotics. After long-term treatment, the mice “exhibited elevated oxidative stress markers in the blood, oxidative tissue damage and up-regulated expression of key genes involved in antioxidant defence mechanisms”, the researchers said.

Having confirmed the culprit as oxidative stress, the scientists sought to prevent it, or to remediate it as it was occurring. They found they could prevent oxidative stress by using a bacteriostatic antibiotic - an antibiotic such as tetracycline that stops bacteria from multiplying but doesn’t kill them. They could also ease oxidative stress by mopping up chemically reactive oxygen molecules with an FDA-approved antioxidant called N-acetylcysteine (NAC), which is used to help treat children with cystic fibrosis.

Dr Collins is planning more animal studies to work out the best ways to remediate oxidative stress. But since both bacteriostatic antibiotics and NAC are already FDA approved, doctors might be using this strategy soon.

The team’s overall goal is to improve the safety of antibiotic treatment. Dr Collins advises, “Doctors should only prescribe antibiotics when they’re called for, and patients should only ask for antibiotics when they have a serious bacterial infection.”

Blood test could be used to diagnose Parkinson's earlier

Researchers have developed a new method that requires only a blood draw, offering a non-invasive...

Cord blood test could predict a baby's risk of type 2 diabetes

By analysing the DNA in cord blood from babies born to mothers with gestational diabetes,...

DNA analysis device built with a basic 3D printer

The Do-It-Yourself Nucleic Acid Fluorometer, or DIYNAFLUOR, is a portable device that measures...