Do you remember your first slime?

Friday, 12 October, 2012

Everyone has their own special method of remembering things. Some use rhymes, some use acronyms and others use good old-fashioned repetition. But when it comes to the brainless slime mould Physarum polycephalum (plasmodium), it relies on the chemicals it excretes.

Researchers from the Universities of Sydney and Toulouse, led by the former’s Christopher Reid, have discovered that plasmodium can navigate through mazes, puzzles and other environments by simply avoiding the extracellular slime it leaves behind. They claim that this brainless, single-celled organism will not backtrack onto its slime trail, recognising that it has been there before. The researchers further note that this is not an automatic process but a ‘choice’ as, when faced with nowhere new to go, the plasmodium will eventually navigate through its slime.

The researchers tested this theory by placing the plasmodium in a petri dish. It was provided with two arms of agar, each leading towards an identical food source. One contained extracellular slime; the other did not. The researchers found that, “When one arm contained extracellular slime, 39 of 40 plasmodia chose the blank agar arm.” However, “When both arms of the Y-maze contained extracellular slime, plasmodia did not show a preference for one arm over the other … indicating that the avoidance response is overridden in the absence of choice.” Thus, the researchers state, it is likely that plasmodium “can sense extracellular slime upon contact and uses its presence as an externalised spatial memory system to recognise and avoid areas it has already explored”.

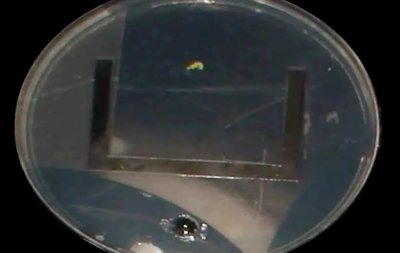

The researchers took this idea further with the ‘U-shaped trap problem’ - often used to test the spatial memory of robots (in fact, their experiment was inspired by the way robots react to their immediate environment). In this instance, the plasmodium was placed in a petri dish with an agar surface, with an acetate U-shaped trap separating it and its food source. The gradient drew the plasmodium towards the trap and it had to find its way out. The plasmodium was tested in two conditions: the agar surface was either blank or already containing fresh extracellular slime. The test revealed that the latter masked the plasmodium’s trail, thus confusing it, causing it to move over its own trail and ultimately slowing it from reaching its goal.

“Of the 24 plasmodia run on a substrate of blank agar, 96% reached the goal within the experimental time limit of 120 h,” the researchers said, “but only 33% of 24 plasmodia reached the goal when the agar was coated with extracellular slime. Of the plasmodia that successfully reached the goal within the allotted time ... those on blank agar found the goal significantly faster than those on agar coated with extracellular slime.” Furthermore, “The average amount of time spent travelling over areas they had previously explored was almost 10 times greater in the extracellular slime-coated treatment than in the blank agar treatment.” This shows just how much plasmodia rely on extracellular slime for effective navigation in complex environments.

Externalised spatial memory has previously been observed in ants and other insects, often via the deposition of pheromones. The use of chemical markers challenges the idea that navigation requires learning or otherwise sophisticated high-level spatial modules; the researchers further challenge this notion by showing that “even an organism without a (central) nervous system can effectively navigate complex environments”.

The researchers believe their work supports the theory that feedback from chemical trails was the first step in the evolution of internal memory for multicellular organisms - a “functional precursor” which allows organisms with primitive information-processing systems to solve tasks requiring spatial memory.

The research has been published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Could this 'PFAS trap' remove the most difficult-to-capture variants from water?

Flinders University scientists have showcased the use of a nano-sized molecular cage that acts as...

What journalists expect from the scientists they speak to

Peer review is often treated as the end of the story, but for journalists it is usually the point...

European Space Agency inaugurates deep space antenna in WA

The ESA has expanded its capability to communicate with scientific, exploration and space safety...