So-called 'dust specks' are actually genome building blocks

An international team of scientists has discovered that tiny ‘microchromosomes’ in birds and reptiles, initially thought to be specks of dust on the microscope slide, are linked to a spineless, fish-like ancestor that lived 684 million years ago. Indeed, they are believed to be the building blocks of all animal genomes, but underwent a significant rearrangement in mammals — including humans.

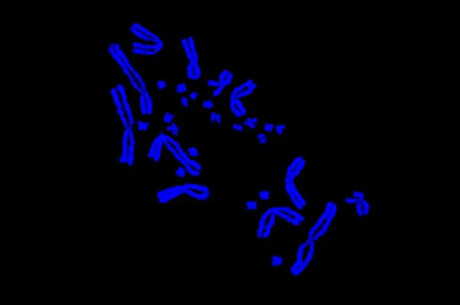

Led by Professor Jenny Graves from La Trobe University and Associate Professor Paul Waters from UNSW, the team made the discovery by lining up the DNA sequence of microchromosomes that huddle together in the cells of birds and reptiles. When these little microchromosomes were first seen under the microscope, scientists thought they were just specks of dust among the larger bird chromosomes, but they are actually proper chromosomes with many genes on them.

“We lined up these sequences from birds, turtles, snakes and lizards, platypus and humans and compared them,” Prof Graves said.

“Astonishingly, the microchromosomes were the same across all bird and reptile species. Even more astonishingly, they were the same as the tiny chromosomes of amphioxus — a little fish-like animal with no backbone that last shared a common ancestor with vertebrates 684 million years ago.”

Dr Waters added, “Not only are they the same in each species, but they crowd together in the centre of the nucleus where they physically interact with each other, suggesting functional coherence.

“This strange behaviour is not true of the large chromosomes in our genomes.”

Prof Graves said in marsupial and placental mammals these ancient genetic remnants are split up into little patches on our big, supposedly normal, chromosomes. Dr Waters added that while we generally think of our own chromosomes as the normal state, mammal genomes have been “hammered” when compared to other vertebrates.

Prof Graves said the team’s findings, published in the journal PNAS, highlight the need to rethink how we view the human genome.

“Rather than being ‘normal’, chromosomes of humans and other mammals were puffed up with lots of ‘junk DNA’ and scrambled in many different ways,” she said.

“The new knowledge helps explain why there is such a large range of mammals with vastly different genomes inhabiting every corner of our planet.”

Please follow us and share on Twitter and Facebook. You can also subscribe for FREE to our weekly newsletters and bimonthly magazine.

AusBiotech and Proto Axiom partner on investor-focused life sciences programs

AusBiotech and Proto Axiom have announced a partnership to strengthen national coordination...

The University of Sydney formalises cervical cancer elimination partnership

The success of a cervical cancer elimination program has led to the signing of a memorandum of...

Noxopharm says paper reveals science behind its immune system platform

Clinical-stage Australian biotech company Noxopharm Limited says a Nature Immunology...